By Yvonne Wright • The Current Contributing Writer

From the beginning of time in the history of humankind, or more specifically, since the Paleolithic Era of the Stone Age, men and women with special abilities and drive for creative work – the artists – have been carrying out an important function in society, often working anonymously until early Modernity.

Prehistoric artists used their knowledge and understanding of the materials available to them intuitively rather than scientifically, lacking organized forms of apprenticeship and schooling, at least the way we understand it today (and which were established millennia later). And yet, artists of the so called ‘primitive period’ were in fact original trail blazers of the creative avant-garde, using the earth’s naturally occurring pigments (sometimes deepened by a heating process) and minerals for painting; stones, clay and animal bones for sculpting; and beads made of seashells for self adornment – head-starting our human evolution into more complex cultures.

These early creative efforts underpinned and enhanced social and religious rituals of the time, at least this is how we today interpret some of the most magnificent paintings and rock engravings found in the Lascaux Caves in France and the Altamira Caves in Spain (17,000 BCE), as being mystically ritualistic expressions of early human reverence for the natural world and fertility.

In truth, Stone Age artists, with their limited resources and working under the extremely dim conditions prevailing in the caves, must have been regarded as true magicians by their contemporaries, capable of creating life-like and anatomically well observed depictions of animals imbued with raw, almost supernatural energy. Often painted on a larger-than-life scale, they covered the walls, floors and ceilings of the rocky shelters. In the Lascaux Caves alone, about 600 painted and nearly 1,500 engraved images of bison, deer, horses and rhinos are still visible and safely preserved.

Interestingly, research conducted by an expert of Paleolithic art, Professor Dean Snow of Pennsylvania State University, has revealed a possibility of a much greater role played by female artists’ in Stone Age art than previously thought. A strong majority of hand print stencils left behind in the caves appear to have belonged to women and some to children, but not exclusively. An interesting observation, that highlights the nurturing importance of mothers throughout millennia, and their important role at awakening in children a sensitivity for creative thinking.

As humanity progressed, the need for art grew exponentially. While civilizations came and went, there were architects, scribes, painters and sculptors, carpenters, blacksmiths, weavers and pottery makers at the core of each cultural, social and economic power toiling away in workshops or at construction sites, producing physical evidence of the ancient world’s advancements in aesthetics that we still admire today.

The first urban settlements rose out of the “fertile crescent of Mesopotamia” (around 10,000 BCE) fundamentally changing the way humans lived up to that point. These early city-states transitioned our ancestors’ lifestyles from nomadic hunter-gatherers to organized communities. It was then, as it is now, that cities became an ideal hub for creative and intellectual thought, places of worship and entertainment, and where new labour divisions and social classes begin to coexist, creating a fertile environment for dynamic artistic productivity.

There were also new benefits of governmental sponsorship in the arts (using the term loosely) first recognized and practiced in ancient Egypt and then continuously present on a grand scale in the Roman Empire, assuring widespread and constant employment for artists.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (d. 322 BCE) once defined art as the realization in external form of a true idea [stemming from] that natural love of imitation that characterizes humans, and the pleasure we feel in recognizing likenesses.

In fact, where would the archeological evidence of the Classical Age of Antiquity and the accomplishments of the Middle Ages be, if it weren’t for the extraordinary artifacts left behind globally, all informed by thousand upon thousands of artists, often working in the shadow of war, conquest and/or social upheaval.

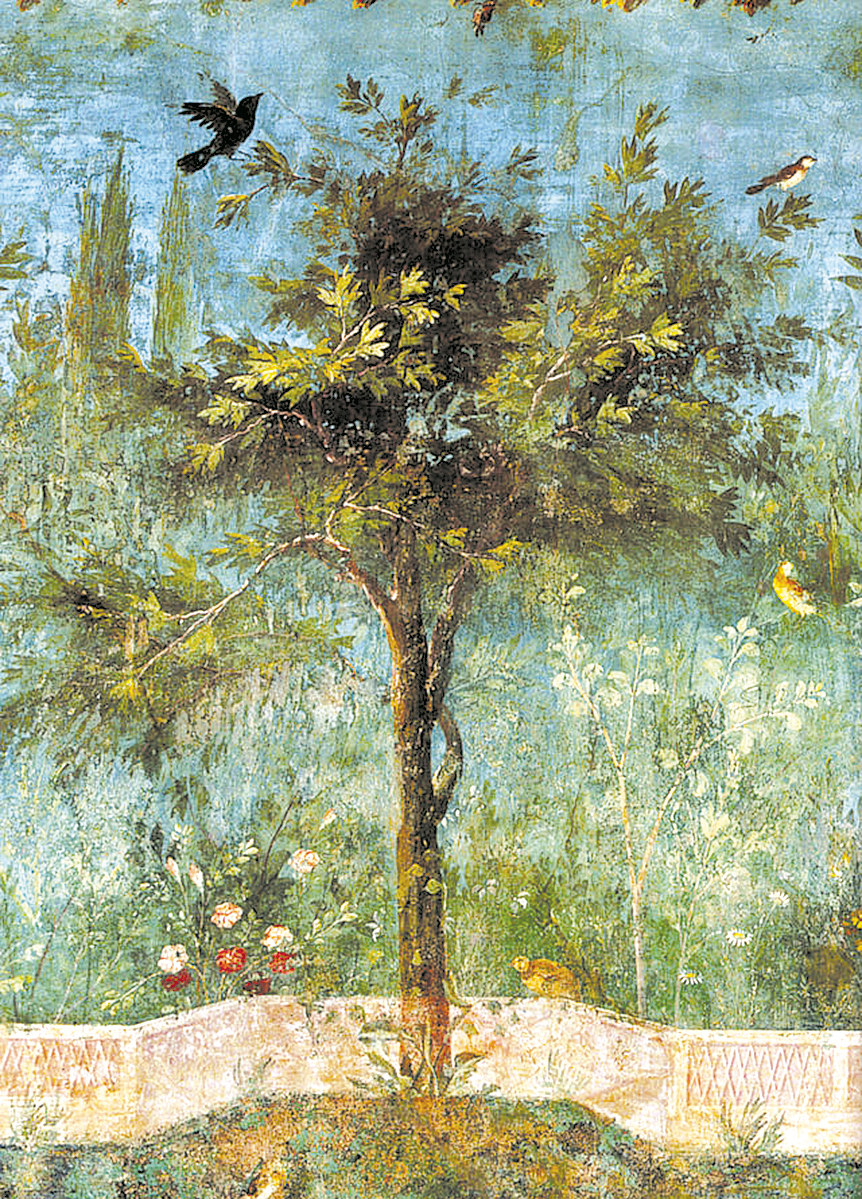

Today, we can still admire the magnificence of Roman frescos, the timeless stylistics of Mayan temples, the weaving quality of Incan textiles, and the subtleties of Chinese scroll paintings from the Song dynasty. We can still marvel at the splendor of Byzantine mosaics, shimmering with gold and Lapis Lazuli, aimed at inspiring otherworldliness, and delight in the intricacy of arabesque art, symbolizing the transcendent, indivisible and infinite nature of God.

Historically, sculpture might have been considered the most popular and durable medium of choice, to which many regional museums can attest. Created in a wide variety of sizes and from various materials, chiseled, forged and molded, their purpose was diverse. From devotional statuettes and bold architectural adornments to imposing effigies of rulers made in order to worship and immortalize them – we have a plethora of evidence to support the notion that sculptors had a paramount importance in serving their communities.

Let us also not forget musicians, poets, actors and orators, playwrights and philosophers who over the centuries, fostered new modes of intellectual expression in words and sounds rather than images.

The emancipation of art came with Modernity, pushing forward the advancement of humanity. The Renaissance ushered in a new way of looking at art, during which time, artists also became more self-aware of the position and influence they held. Rejecting anonymity, prevalent for centuries, they began to be called ‘masters’ (maestros in Italian), after completing years of professional training, apprenticeship at reputable artists’ workshops, and joining the guilds (an early equivalent of unions).

However, it was a bumpy road to reach the prestigious position contemporary artists enjoy today. Young Michelangelo Buonarroti, who later became one of the greatest artists of all time, was often beaten by his father and uncle for attending studio apprenticeship, because they feared an artist in the family would disgrace the family name.

By the late 1700s, and before the industrial revolution automized and replaced time honored skills, many artists around the world rose to high social positions based on their technical and creative competence. Unfortunately, cheaper manufacturing processes and various economical and political factors reduced the need for hand made furnishings, hand painted portraits, traditionally woven tapestries and so on, to such an extent that many of these highly developed abilities became redundant and lost to time. For example, today it is impossible to recreate the genius behind the violin instruments made by Antonio Stradivari 300 years ago – still the preferred instrument of choice for many highly accomplished performers, and fetching as much as $16 million USD for an original.

The 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant qualified art as a separate entity from craft, and argued that its purpose was to be “purposeless,” or a purpose in itself. Others argued that the purpose of art is self expression – art for art’s sake – which became a popular Bohemian mantra in 19th century Paris, popularized in North America by painter James Whistler. Marxist ideologists of the early 20th century have proposed that art should be politicized to serve moral and utilitarian function in society, striped of any transcendental values.

The 21st century narrative in art predominantly strives to address social, political, economical and environmental issues, with an emphasis given to personal, subjective and visionary dialogue. Contemporary artists live in a world that (for most part), allows their personal creeds and beliefs to freely inform their work without fear of retribution.

The practice of creative arts in the United States has been lively and exciting for over two centuries, and a home to highly exceptional visual and performing artists, working in a variety of styles.

One of Pennsylvania’s long standing artistic groups is our local Carbon County Art League (CCAL), a nonprofit organization that supports artists of all ages and practicing all mediums. Its goal is to inform and educate about art, as well as to encourage the public to appreciate and support local artists through the purchase of their works. On May 8th, 2021, CCAL will be hosting their 39th Annual Art Show, which, due to Covid19 restrictions will be held virtually for the first time. To learn more about the art exhibit, please visit https://carboncountyart.wixsite.com/carbon-county-art.

Today’s artists, like those that came before them, are one of the backbones of their communities, carrying, if only symbolically, the most important function placed upon their shoulders, the cultural legacy of their civilization.

Yvonne Wright is the owner of STUDIO YNW at 100 West Broadway in Jim Thorpe. She can be reached at studio.ynw@gmail.

Add Comment