By Yvonne Wright • The Current Contributing Writer

In the northern hemisphere, the arrival of Autumn marks the end of the most leisurely enjoyed time of the year. It’s an intermediary season between summer and winter, during which the majority of plants begin to turn brown and wither. Temperatures gradually decrease and deciduous trees present a lush spectacle of colorful foliage in a variety of gold and red hues. Falling between September 22 (autumnal equinox) and December 21 (winter solstice), the Autumn season alters the physical conditions of the natural world and is most acutely observed by agricultural and farming communities.

In fine arts, the binary nature of Autumn has often been associated with a feeling of nostalgia brought upon creative souls by the wilting of plants, ‘emptying’ of harvested fields, and the impending feeling of winter’s chill to come. At the same time, there is also a desire to document this fleeting natural beauty with depictions of a plentiful promise and national pride in the rural setting, creatively expressed by many artists.

The latter, called themselves Regionalists, art movement proponents that emerged in Midwestern America in the early 1930s as a new type of modern art, and one that has deep roots in American heritage and the romantic landscapes of the Hudson River School. At their height of popularity, the Regionalist artists drew most of their subject matter inspiration from farming communities and regional landscapes, advocating for the figurative painting of rural Americans. It was a type of artistic philosophy that centered its aesthetic narrative on traditional American values. They portrayed lifestyles as symbols of the strength and endurance of the American people, made popular during the Great Depression (1929 – 1939).

From an art historical perspective, Regionalism is often considered “a reactionary movement” because it rejected the avant-garde art of Picasso, Matisse, Duchamp, and other European artists in favor of a “more representational, realist style” as an expression of new American contemporary art. The rejection of European Modernism was “largely symptomatic of the prevailing desire to create an indigenous, modern, American art that was free of foreign influences.”

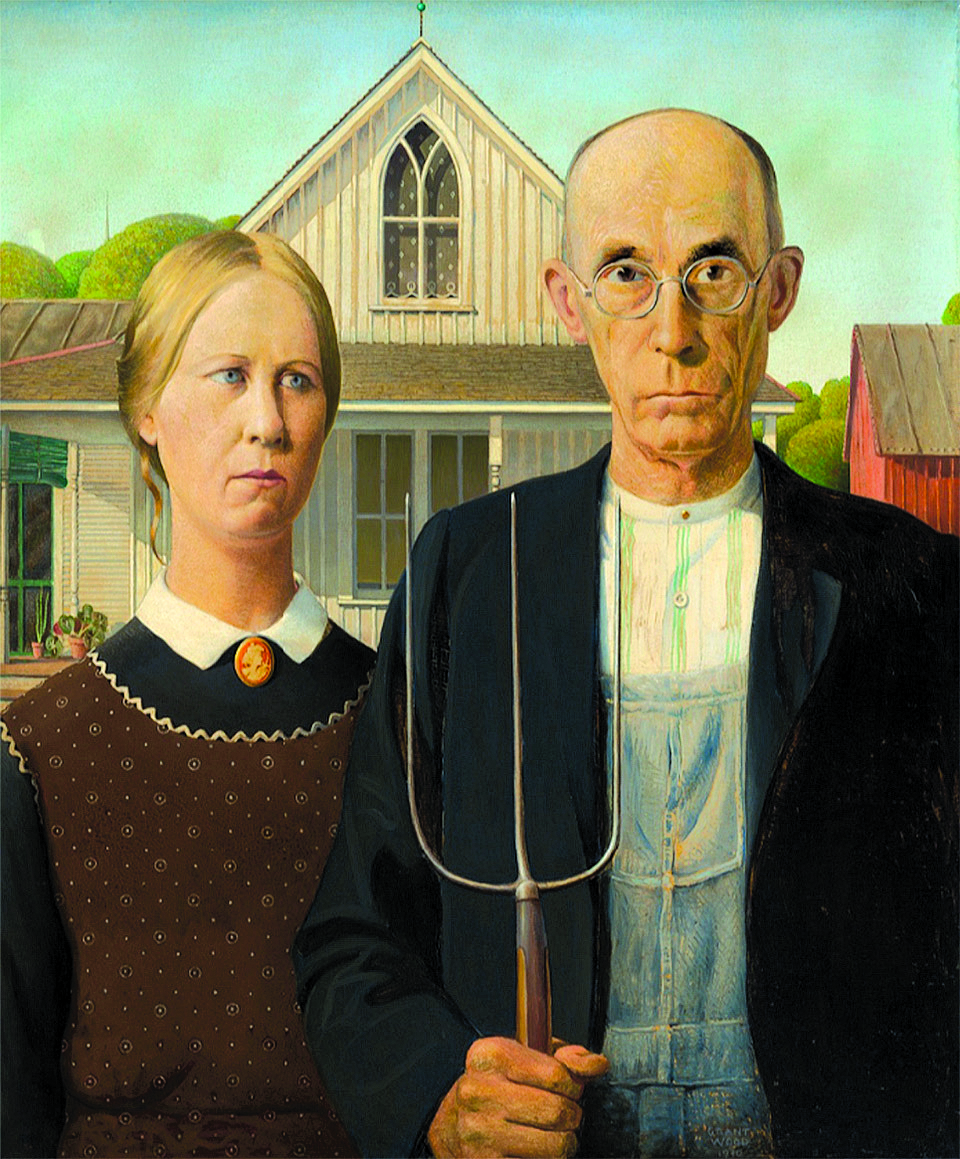

The movement’s leader and a great proponent of regionalism in the arts was Grant DeVolson Wood, best known today for his internationally recognized iconic painting “American Gothic” (1930). He was a realist artist, as he adhered to an artistic movement inspired by subjects from everyday life and painted in a naturalistic manner. He worked in many creative mediums – from lithography, ink, charcoal, ceramics, metal, and wood to found objects – and specialized in depicting the agrarian life of Iowa.

Born in 1891, Wood grew up and lived his entire adult life in Cedar Rapids, IA. Artistically active since he was a small boy with an inquiring mind, in 1913 Wood enrolled in the prestigious School of the Art Institute of Chicago to study contemporary art. After graduation, in the final stages of World War I, he joined the US military to work as an artist designing camouflage scenes and propaganda art.

Wood made several trips to Paris between 1922 and 1928, where he studied various painting techniques, especially Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. But, it was the work of 15th-century Flemish artist Jan van Eyck, which Wood saw at the Louvre, that helped him to define his own painting technique and future direction in art. With his bohemian days in Europe behind him, Wood took an art teaching position in 1934 at the University of Iowa School of Art and Art History, where he became a key part of the school’s cultural community, until his death in 1942.

An avid Freemason, Wood received the 3rd Degree of Master Mason in 1921. The title symbolizes man’s maturity in life and his increase in knowledge and wisdom. Many of his works were informed by Freemasons’ moral and ethical beliefs — particularly expressed in 1932 when Wood helped to co-found the Stone City Art Colony near Cedar Rapids, “an alternative to more established artist colonies in Woodstock and Santa Fe,” in an effort to help Midwest artists get through the Great Depression. However, plagued by financial difficulties, the colony closed in 1933.

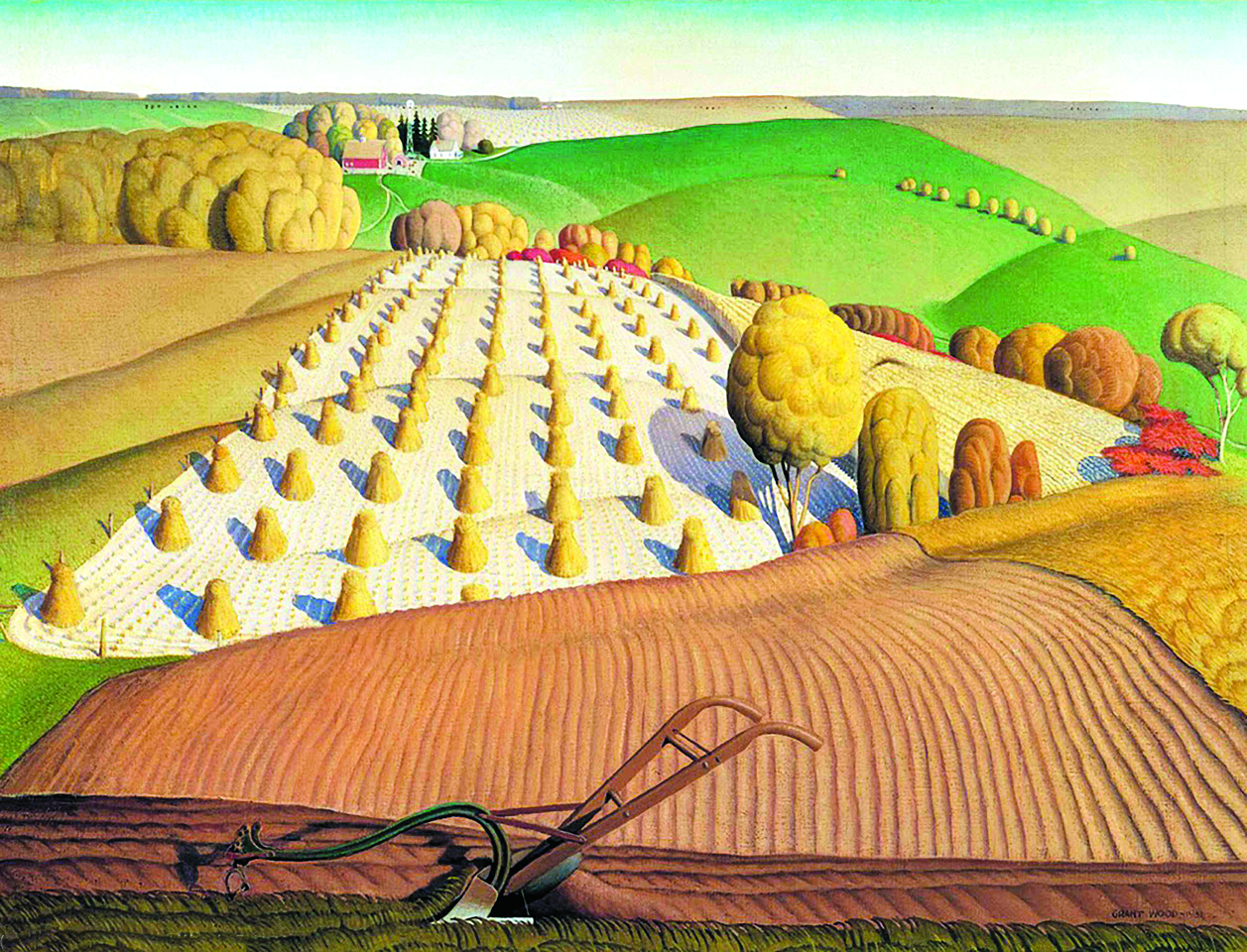

The 1931 Grand Wood painted “Fall Plowing,” which is still considered a key work of the Regionalist movement. Executed in oil on canvas, the artist’s early work typifies Wood’s fondness for Iowa’s rural landscape and the quiet dignity of his state’s agriculture-based economy. The work’s compositional strength rests on its streamlined, geometrical balance between the land and the sky, garnished with elegantly rendered, sporadic detail. It suggests the aesthetic influence of Bruegel and other Northern European Renaissance artists whose works the artist studied during his trips to Europe. Wood’s painterly style is also informed by art deco and cubist movements but applied in his own, unique way. These styles are particularly noticeable in his treatment of trees, sheaves, and buildings.

Focusing on the harvest in progress, “Fall Plowing” seems to advocate the importance of new technologies in the development of prairie lands into workable farmland. Woods indicates that by the John Deere steel plow, proudly displayed in the foreground. The painting’s composition promotes a balance between the plowed land, harvested fields, and grassy hills, yet untouched by human intervention. Perhaps the artist intuitively alludes to the beginning of the Dust Bowl phenomenon, the greatest ecological disaster in the history of the United States. It started with the onset of drought in 1931 and lasted for five years, exposing the bare, over-plowed fields of the Great Plains to massive erosion.

In “Fall Plowing,” the soaked-in-the-afternoon-sun Autumn landscape is ubiquitously still. It’s as if the crops’ long shadows have paused upon a dry field, suspending nature and industry temporarily in a delicate equilibrium. It is both an optimistic celebration of a plentiful harvest and better times to come. Or, perhaps, it is Wood’s subtle warning about the state of the American farming industry and the existential challenges it created during the Great Depression.

Upon completion of this painting, currently displayed at the Figge Art Museum in Davenport, IA, as part of the John Deere Art Collection, Wood became increasingly more aware and proud of his American Midwestern roots. Promoted by conservative critics along with other Regionalist artists like John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton, Wood positioned himself at the center of a hotly debated and criticized artistic spectrum.

Grant Wood left a legacy as one of the greatest American painters, whose works bridge the gap between stiff academic realism and modernism. He has created some of the most iconic works that now symbolize the country and helped to pave the way in establishing a new, individualistic identity for the 20th-century American art.

Yvonne Wright is the owner of STUDIO YNW at 100 West Broadway in Jim Thorpe. She can be reached at studio.ynw@gmail.com

Add Comment