By Yvonne Wright • The Current Contributing Writer

“The hen cackled in the early morning light as the door of the chicken coup opened and the boy walked in with his basket. He had risen before dawn to help with the farmwork. But on this most auspicious of days, Karfreidaag, or Good Friday, gathering the eggs was no mere ordinary task.”

– Patrick Donmoyer

Although widely popular throughout North America today, the state of Pennsylvania was the original point of entry into the New World of the Easter egg tradition. German-speaking immigrants in the early 1700s were among the first to introduce this vibrantly creative folklore, symbolically associated with the Christian Paschal Feast of Eastertide (Easter) to neighboring communities. Over the decades that followed, numerous ethnic groups from Europe arrived to the United States, bringing with them culturally specific traditions of celebrating Easter, among them the practice of decorating, blessing and eating Paschal eggs as part of their heritage.

Whether settling in the urban centers of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, or in rural regions of northeastern Pennsylvania, 19th century central-and-eastern European immigration gave rise to many egg-related practices for celebrating Easter, including Easter Rabbits, egg hunts, Easter baskets and egg rolling, which are still very much present and continually held dear by many Americans today.

Foreign at first, unfashionable and too secular for the tastes of Quakers, Puritans, Presbyterians and other sectarian communities in Pennsylvania, the tradition of painting eggs at Easter eventually spread throughout the continent, carried forth by settlers and a burgeoning new industrial economy. Yet, the practice of embellishing eggshells is quite ancient, and examples of such have been found in Egyptian and Mesopotamian tombs. Considered special, even magical, the tradition of using eggs in rituals is archeologically well documented.

In medieval England, on the Saturday before Lent, there was a common practice for children to go door-to-door asking for eggs. In Modern times, the custom of children searching for eggs on Easter morning was substituted with egg-shaped chocolates, and plastic egg containers filled with candy as treats to be found; sometimes with prizes given for the largest number of “eggs” collected.

The first chocolate eggs appeared in France at the court of Louis XV in 1725, becoming a fanciful desert sensation of the aristocracy. But it took the English to democratize this culinary delight by manufacturing the first chocolate Easter eggs on an industrial scale in 1875, after Cadbury successfully developed a revolutionary pure-cocoa butter that could be moulded into shapes and filled with dragées (sugar-coated nuts, fruit pieces or candy beads). In Italy, due to a traditional love of chocolate as an important part of everyday life, chocolate Easter eggs range from tiny solid milk chocolates to surprisingly massive, hollowed out eggs that may contain elaborate gifts.

One of the enduring Pennsylvania Dutch contributions to our modern celebrations of Easter in North America is the character of Oschderhaas – the Easter Hare (a future embodiment of the Easter Bunny). Each spring, children believing in an egg-laying rabbit, would make nests in the garden for the hare to lay its colored eggs. He was introduced to the newly blossoming American cultural identity in the early part of 18th century, along with Easter baskets, which were customarily exchanged in German-speaking communities.

Historically, however, egg-bringing Bunnies and their fluffy, yellow chick companions in gardening hats, all have Anglo-Saxon pagan roots associated with the Spring Equinox and worship of the pre-historic goddess Eostre or Ostara (a deity of spring, fertility, dawn and new life). She is credited with transforming a bird into a hare, and the hare responding by laying colored eggs – indicative of nature’s rebirth and fertility after long winter months.

Early Pennsylvania Dutch settlers shared a belief that eggs laid on Good Friday were intrinsically holy. Some were to be eaten for breakfast on Easter morning to prevent illness, while others were set aside unadorned, with only a particular year inscribed on them, for their protective powers. Such “Good Friday eggs” were hidden in containers, often in attics, to bless the household, being consecrated by virtue of this special day. “Ordinary eggs” were dyed and decorated on Holy Saturday in preparation for Easter the following day.

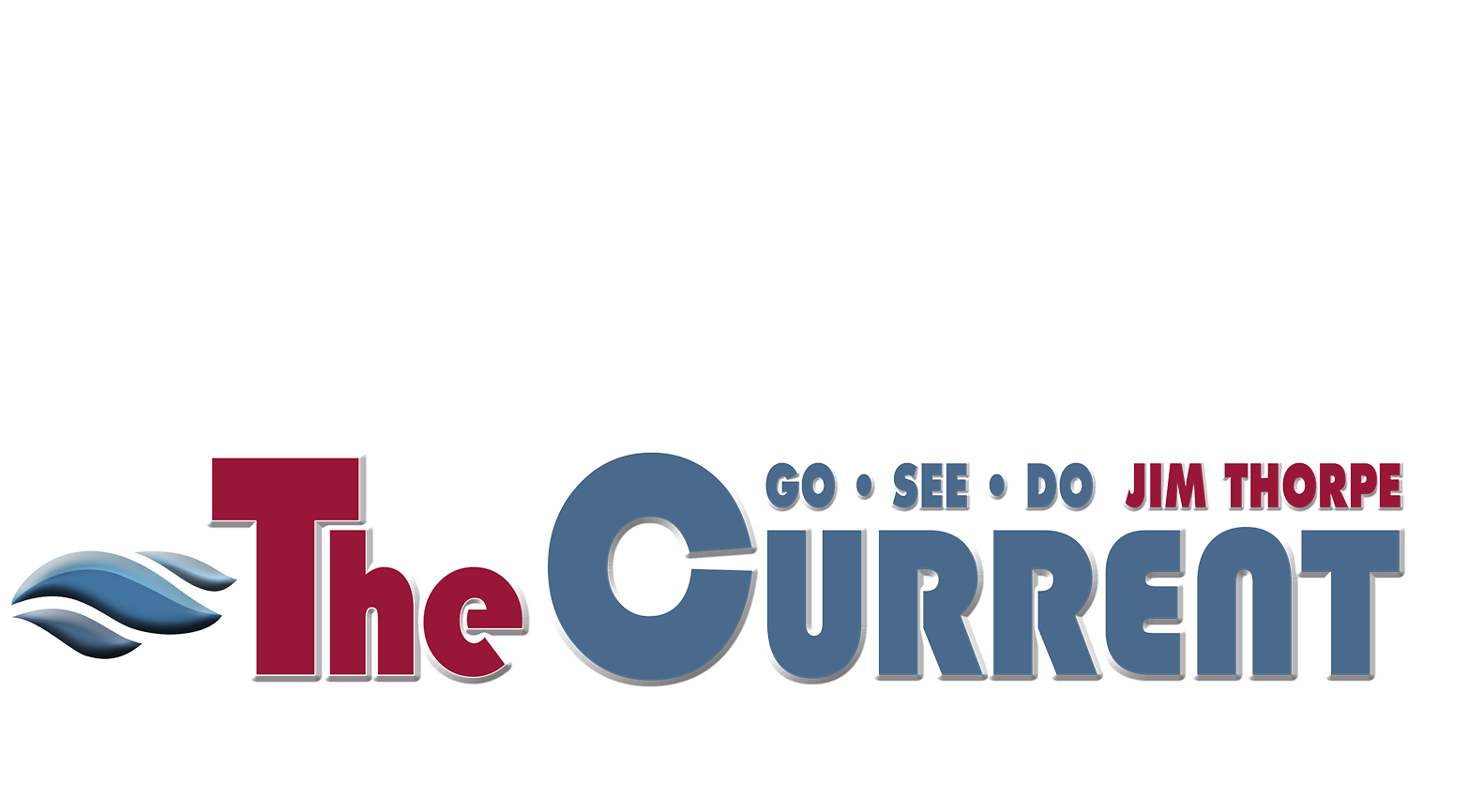

Whole families, participated in this delicate art form. Among the Pennsylvania Dutch, like their relatives in the “old country”, the most common way to dye eggs was to hard-boil them in onion skins and vinegar to produce a range of colors from orange to deep red or brown depending on the concentration of the dye and whether the hens laid white or brown eggs. Other colors were historically produced from black walnut hulls or oak bark for shades of deep brown to black; hickory bark for yellow; red cabbage [after oxidation] formed a deep green; reconstituted juices of elderberries, currants and poke for shades of magenta; and a wide range of herbs and roots such as turmeric or beets for yellow and pink. The palette of reds was especially popular at Easter, because of the color’s association with the blood of the crucified Christ shed on Good Friday; a symbolic declaration of the Christian belief that Jesus died for the sins of humanity, and defeated the powers of death through His resurrection.

Not only chicken eggs were dyed in multiple colors, but also goose, duck, turkey, guinea fowl and peahen eggs. In addition to coloring their shells, many eggs were delicately decorated by scratching their surface to reveal the white of the shell underneath. Some eggs were inscribed with initials and dates by the artisans who made them. Such artistic renderings were usually set aside as special gifts to family and friends. Floral and bird patterns were the most popular, along with images of angels, people, animals or abstracted forms.

The ephemeral nature of egg-decorating became a subject of cultural scrutiny in the late 19th-century by newspapers throughout southeastern and central Pennsylvania; editors queried their readers about finding, and therefore preserving for posterity, vintage eggs still in the hands of local communities. The survival of a 100 year-old Easter egg created a sensation when reported by the Lancaster Daily Express on March 27, 1875. It was delicately decorated just three days before the battles at Lexington and Concord at the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775. In 1909, it was reported that master stonecutter and painter, Enos K. Newman of the Schwenkfelder community of Upper Perkiomen in Montgomery County, had in his possession an extensive collection of Easter eggs made by several generations of his family, the oldest having been created in 1808.

Coal, steel and railroads transformed 19th century Pennsylvania into an industrial power, enticing more immigrants from Europe and other parts of the world to settle within its bustling industrial communities. The coal region of the southeast became home to many Ukrainians, Poles and other Slavic groups whose integration of daily life with church liturgy produced a robust and spiritually reflective tradition at Easter involving intricately decorated eggs, created in a variety of styles that were central to preserving portions of the life and cultural identity of their European roots.

The word pysanky (singular pysanka) comes from the Ukrainian verb pysaty, meaning “to write” or “to inscribe” and reflects the way their famously detailed egg-designs are achieved. It is a wax-resist method in which the artisan uses a stylus to apply wax to an egg shell to create patterns, masking many layers of color from successive dips into a dye bath. Designs range from distinctive geometric shapes to floral and religious images. Many pysanky are regarded as culturally specific works of art, but for their creators they are folkloric expressions of goodness and blessing, not only to one’s own family and home but also to the entire community and the world itself.

Typically, Ukrainian families begin decorating their eggs early in Lent, to assure an abundant supply for the many social and religious functions observed. Their Easter-eggs fall into two traditional categories: a) krashanky – simply dyed red, yellow, green or brown, and b) pysanky – works of art painstakingly made over a period of many weeks. Both types of eggs would be brought to church to be blessed, alongside bread and small portions of each type of food from the Easter table. Some of the oldest traditional pysanky-designs are known to predate Christianity and are rooted in ancient agrarian cultures that saw the egg as a symbol of new life.

Observably, these colorful and superbly executed traditions found their way into all corners of the continent, informing contemporary expression of American holiday traditions. Pennsylvania’s diverse ethnic communities continue to inspire us with the aesthetic values of their folk culture. In an ever-changing world, new generations of artisans are ensuring that these precious artistic expressions are protected from vanishing forever from the commonwealth’s complex identity, bringing a kind of inner equilibrium to a hastened modern world.

Yvonne Wright is the owner of STUDIO YNW at 100 West Broadway in Jim Thorpe. She can be reached at studio.ynw@gmail.com

Add Comment