By Yvonne Wright • The Current Contributing Writer

As cold December breezes serve a final blow to lingering memories of summer, with chill and snow comes a heart warming anticipation of Christmas. Expectations are high and for the most part traditional, comforting and reassuring; filling our hearts with a sense of happy togetherness and a hope for joyful feasting ahead. Urban, and rural communities alike, are set aglow during this time of the year, with strings of lights decorating streets, buildings and trees, piercing through wintery darkness with a friendly glow.

The abundance of visual stimuli intensifies with the first signs of lavishly decorated evergreens. Some can be visible through the windows of residential neighborhoods (seemingly inviting us in, with a promise of warm hospitality), while others, splendidly decorated, compete for our attention in public spaces. Soon, there will be sounds of happy caroling thrown into the mix of lively community hustle and bustle – all heralding to the world a season marked, for the most part, by a pleasantly plump, white-bearded Santa in a red suit.

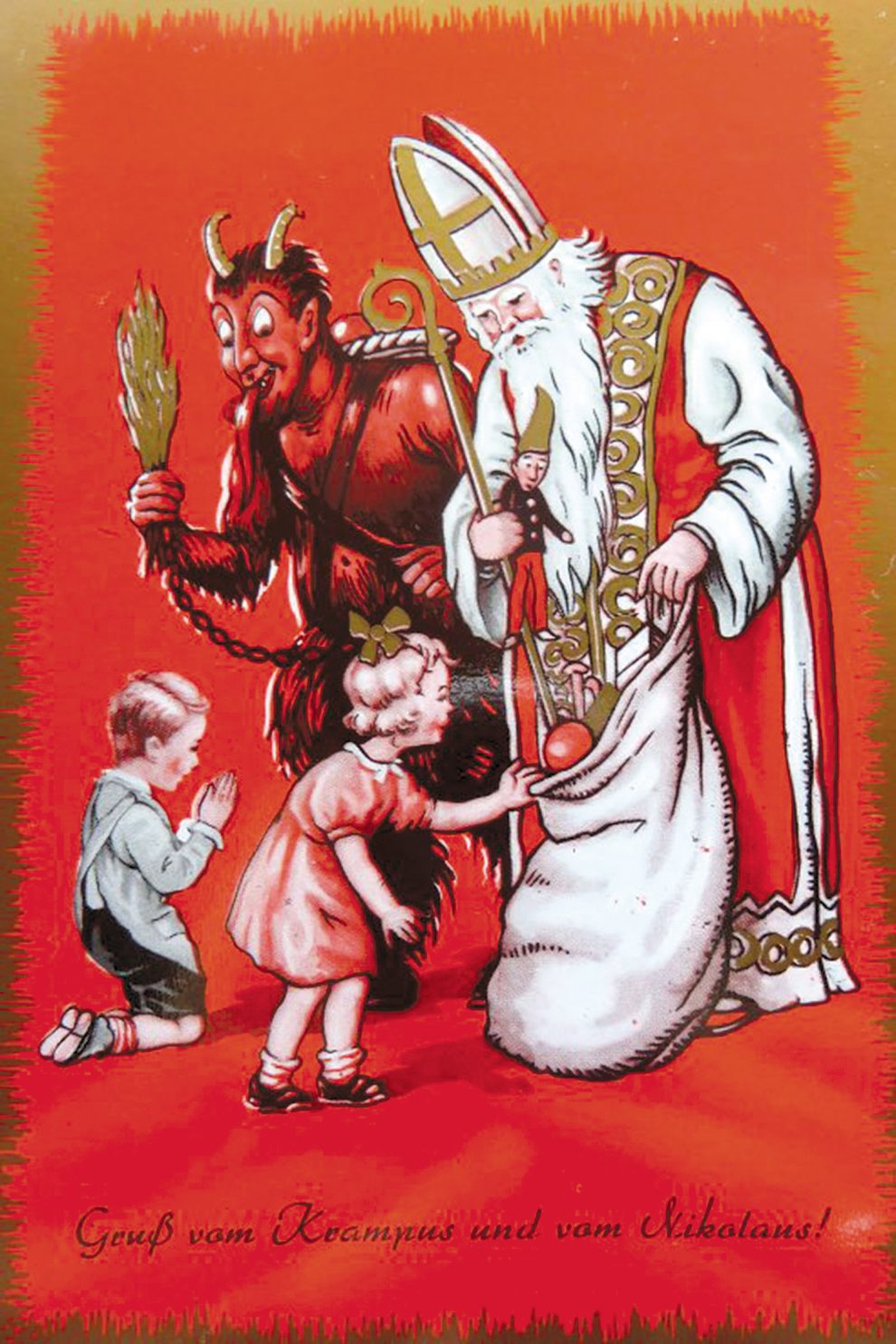

Accustomed to his gregarious presence and genuinely enjoyed by generations of children in the United States awaiting his arrival the days before Christmas with pleasurable expectations, the gift-bearing Father Christmas/ a.k.a Saint Nick/ a.k.a Santa Claus usually makes his way down through the chimney when everyone is asleep to deliver the goods. As a purely fanciful character (dressed in a red jacket garnished with white fur, loosely fitting red pants, bootstrap leather boots and a wide leather belt around his belly), Santa has evolved relatively recently from the legendary Saint Nicholas, the 4th century Bishop of Myra, and a patron Saint of sailors, merchants, repentant thieves and children. Born to wealth, he was credited in his lifetime for ubiquitous generosity and kindness, and is often portrayed in liturgical garments of the early Christian Church.

The tradition of St. Nicholas as the benevolent gift-giving bishop was brought to North America in the early 1600s by Dutch settlers, who celebrated Sinterklaas on the 6th of December with a simple gift-giving tradition to “preserve a Christmas Day focus on the Christ Child,” offering a spiritual dimension to gift-giving. After years of mispronunciation, the Anglicized version of Sinterklaas turned into Santa Claus.

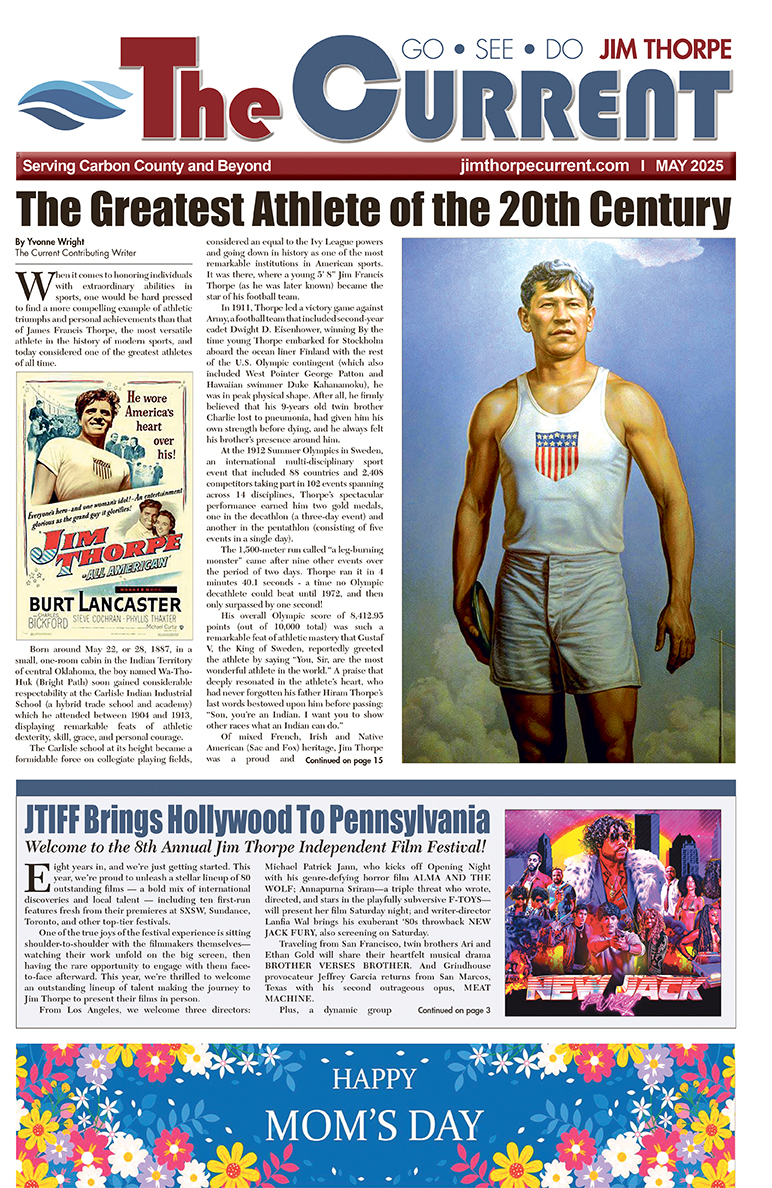

In 1931, the Coca-Cola company commissioned artist Haddon Sundblom to create an image of a wholesome, but fun, Santa Claus to promote their products. Inspired by Clement Moore’s 1822 poem, the image of a pleasantly plump elderly gent in a red suit was born, setting the standard for future renditions.

Interestingly, in recent years there has been a resurgence in popularity of a sinister looking companion to St. Nicholas…. his legendary dark servant, Krampus, who haunted European children for centuries. According to Patrick Donmoyer of the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University, the character of Krampus sprang from ancient pagan traditions deeply rooted in Austrian and German folklore, still very much present in European Christmas celebrations today. During reenactments of St. Nicholas’s Christmas visits dressed in bishop’s vestments and mitre, the shadowy presence of Krampus “provides the counterpoise of punishment” as a grizzled companion to the kind and generous bishop.

Donmoyer remarks that American children should consider themselves lucky for not living in Austria, because it is there that a ghoulish Krampus is said to wander the streets and knock on doors in search of badly behaved children to punish them. Early December, one can expect to encounter a terrifying masked figure with horns wandering about with a bundle of sticks scaring local communities. In 2011, residents of the greater Philadelphia area started their own Krampuslaaf parade, inspired by the dark side of European holiday traditions, catering to a diverse, theatrical young audience with a taste for heavy metal music and neopaganism; today continuing as part of the Parade of Spirits (a.k.a der Geischderschtrutz), that includes other aspects of Germanic lore and similar traditions from cultures around the world.

Good and jolly old Santa has dominated the American Christmas scene for over a century, but his domain seems to be decreasing of late, as many Americans begin to seek holiday thrills outside their traditional cultural milieu. Intrigued by unconventional options, they delight in strange processional displays of revelers in horned costumes, whose punitive, terrifying looking characters, sometimes appear together with St. Nicholas, who brings the gifts.

Few Pennsylvanians may be aware today that “the commonwealth is the New World point of origin of an equally legendary and fearsome figure known to the Pennsylvania Dutch as the Belsnickel.” An archetype of the Wild Man, popular throughout Europe, he is typically clad in furs, dressed in patched and tattered clothes, masked, smeared in soot, carrying a whip and waving a bundle of birch switches. Crowned with horns, the Belsnickel serves as both the bearer of gifts and an agent of punishment in the Pennsylvania Dutch Christmas tradition.

Long before Santa Claus, a neighbor or member of the family would play the role of the Belsnickel, but kept his identity secret from the children, who were meant to be delighted and terrified at the same time by his visitation, in an effort to prepare them for the coming of Christmas.

“In a time when presents were sparingly given,” explains Donmoyer “the Belsnickel rewarded well-behaved children with nuts, cookies or candy, while children prone to roguery were threatened with the switches. The Belsnickel distributed the candy by throwing it across the kitchen floor, and this practice served as a test of sorts. If children practiced restraint, they were rewarded. If they were too eager or greedy in reaching for it, […] they received the Belsnickel’s wrath.” Which was often a frightening experience for the children, but humorous for the adults.

As Donmoyer’s research indicates, visits from the Belsnickel were not exclusive to rural Pennsylvania: “The urban phenomenon was further enhanced by the belsnickelers’ use of the railroad to travel incognito into neighboring towns.” As reported by the Harrisburg Telegraph on December 26, 1879: “Bellsnickels in the most outlandish costumes were out in droves. They infested the stores and played on antique instruments as a prelude to passing round the hat, and generally departed with a parting salute on their tin horns. Some were quite proficient as musicians…but the majority were simply frightful….We regret to say that some of them were the worse for liquor.”

Less fearsome than the Krampus, belsnickeling in Pennsylvania was an opportunity for people, especially youths, to override some of the normal rules of social order, providing a communal context for releasing social tension, exploring alternate identities, and breaking the mold of the mundane.

By the early 20th century, most Americans were expecting visits from Santa Claus, rather than the Belsnickel, or Krampus, who were eclipsed and generally faded from the Christmas holiday narrative in the United States; and yet, they persist in numerous community celebrations, festivals and Christmas markets throughout Berks, Lebanon, Lancaster, Lehigh and Montgomery counties, to terrify and delight thousands of Pennsylvanians each year.

A growing number of Pennsylvanians appear to find the Belsnickel or Krampus persona to be a deliciously exotic and more exciting experience than benign visits with Santa Claus in local shopping malls. These characters once again provide an opportunity for upending social imperatives, and for challenging the predictability of a holiday fraught with social expectations, reflecting a tension between traditional values and an increasingly homogenized American Christmas experience. If interested in the tradition, check out the Black Forest Krampustnacht Festival in Jim Thorpe, PA, to be celebrated on Saturday, December 4th at Kemmerer Park, between 1 pm and 6 pm.

Yvonne Wright is the owner of STUDIO YNW at 100 West Broadway in Jim Thorpe. She can be reached at studio.ynw@gmail.com

Add Comment