By Yvonne Wright • The Current Contributing Writer

Conversely, in the realm of a genuine appreciation of what previous generations have done for us, seldom does historic content enter our consciousness where women’s artistic contributions are concerned. And yet, the inexhaustibly fertile soil from which contemporary visual culture sprouts in its diversity today would not be possible if not for the pioneering spirit of 19th and early 20th century artists, many of whom were women, whose efforts, courage and determination opened ways for others to follow.

The last decades of the 19th century were particularly marked with an abundance of talented painters and sculptors, as if the gates of fine art productivity suddenly burst under creative pressure, fertilizing generously both genders and reaching across social backgrounds indiscriminately.

Fin-de-siècle (end-of-the-19th century) was an era of change, and a turning point in the history of women artists. Whether they were aristocratic socialites, industrial heiresses, middle class wives or bohemian romantics, many accomplished much. For some, professional recognition came posthumously, while others vanished into obscurity in spite of their gifts. Inadvertently, their life experiences amounted to a rich intellectual legacy for all women, creating a frame of reference for future generations of artists. Many wealthy philanthropists in the age of industrial expansion, as well as middle class art collectors and connoisseurs, come to prominence during the 1870s, enabling dramatic art market growth with widening art acquisitions. Their social presence in Europe and North America indicated the western world’s prosperous economy with an appetite for cultural sophistication.

Affectionately categorized as the American Gilded Age, roughly coinciding with the Victorian Era in Britain and the Belle Époque in France – this unique cultural merging of art and commerce during the 1870s through the early 1900s, quickly established cities like Paris, New York and London as cultural leaders, and a kind of ‘judges of elegance’ for the western world. New possibilities opened up for women artists with the advent of modern art schools. The privileged destination for studying art was Paris – living and studying there meant the greatest possibility for success. Many young American men and women flocked to the city in the hopes of being discovered. They joined ever-expanding international artistic circles, whose dreams, passions, despairs and successes signified the alluring spirit of the city, with its power to elevate, or to destroy.

Several private Parisian art schools and artist-run ateliers (workshops/studios) offered professional training and most of them admitted women, although in limited capacities. Internationally popular and particularly frequented by American students was L’Académie Julian, offering painting and drawing classes taught by well established artists of the time. For women, this school presented an opportunity to receive academic training that permitted them to draw from nude female and partially-clad male models, but they were not allowed to share the same studio spaces with their male colleagues. Whereas the highly regarded state-run École des Beaux-Arts, known for the highest standards for education, actively excluded women until 1897. Visits to art museums like the Louvre were highly recommended forms of professional development and meeting places for French and American female art students, who were not allowed to attend cafes where the avant-garde elite socialized. The Gazette des Femmes claimed in 1883 that 300 North American female art students came to Paris each year, and many experienced a new kind of social mobility and independence beyond domestic femininity.

For American art students studying at home, various options in art programs were available at newly coed colleges and universities, as well as at the first prestigious women’s colleges such as Vassar, Smith, Wellesley and Radcliffe which opened in the second part of the 19th century. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia (PAFA), the first and oldest art school in the United States (founded in 1805), offered the fundamentals of drawing, painting, sculpture and printmaking.

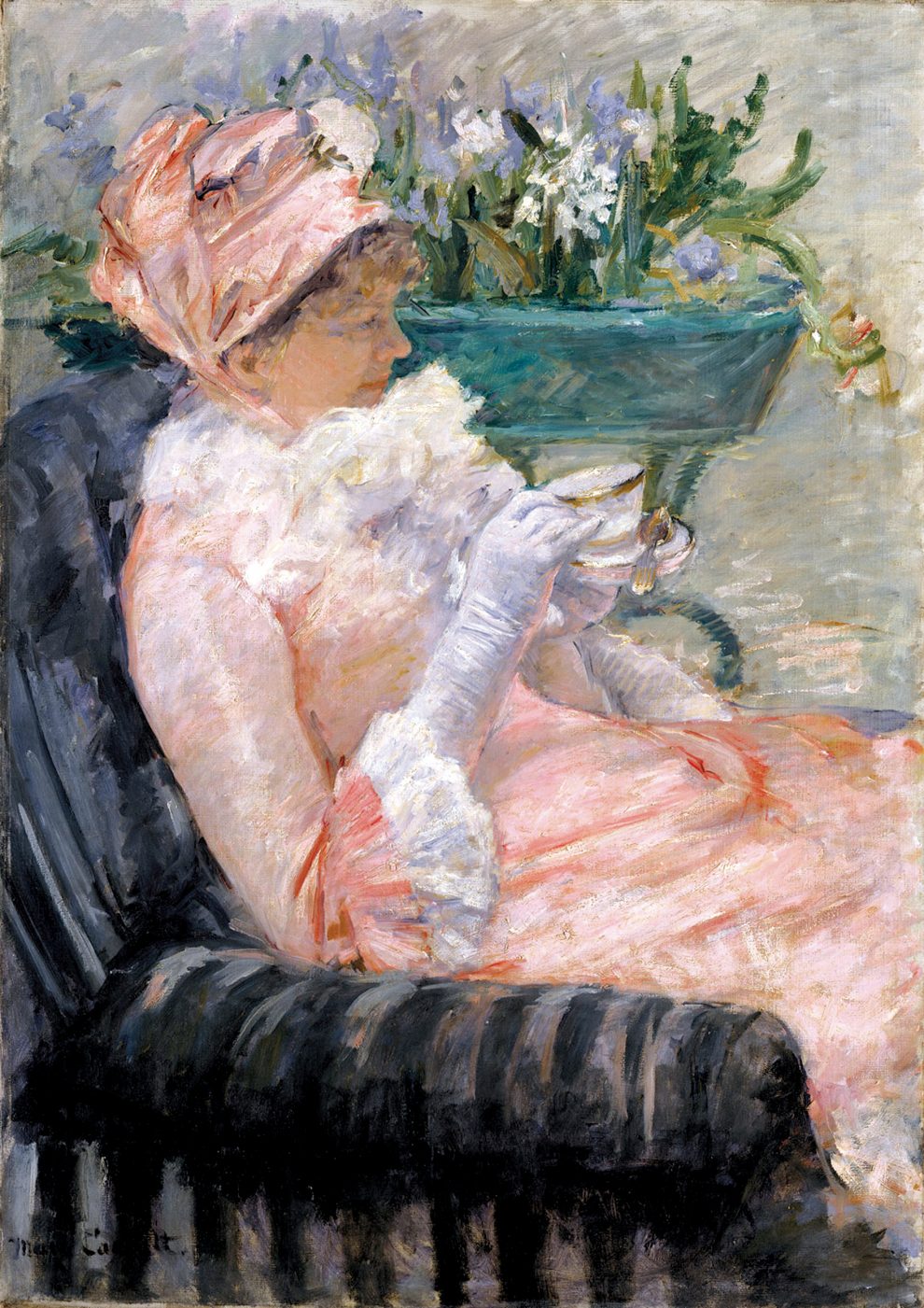

Mary Cassatt, a Pennsylvania native and renown American painter and printmaker, entered PAFA at the age of 15 and continued her studies there during the turbulent years of the Civil War – determined to become a professional artist in spite of her family’s objections. Chaperoned by her mother, she eventually moved to Paris where, on Edgar Degas’ invitation, she joined the Impressionist group alongside another talented woman in the group, Berthe Morisot. Being tutored by an established artist was another form of professional training available to women in the 19th century and Mary Cassatt developed her mature style under the tutelage of Degas. In time, Cassatt became a role model for many young American artists who sought her advice, and served as an advisor to major American art collectors, encouraging them to invest in modern art, especially Impressionists. In 1904, in recognition of her many contributions to the arts, the French government awarded Cassatt the Legion d’honneur, the highest French order of merit.

The late-19th and early 20th centuries showed a remarkable growth of formally trained women artists who successfully found their own voice in a profession that had been monopolized by males for centuries. Their brushes and chisels are idle now, but let us remember with pride those pioneering women, who dared to be artists, defied their limited roles in society, and aspired to be equal to men.

Yvonne Wright is the owner of STUDIO YNW at 100 West Broadway in Jim Thorpe.

She can be reached at studio.ynw@gmail.com

Add Comment