By Jack Sterling

Special to The Current

In the cold and snowy December of 1817 three business partners rode north from Philadelphia, headed towards the valley of the Lehigh River. The partners were Josiah White, Erskine Hazard and George Hauto, and they were taking a great risk. They were planning to invest in the coal lands in the nearly uninhabited wilderness beyond the Blue Mountain; a place that Moravian missionary Count Zinzendorf had dubbed “St. Anthony’s Wilderness” one hundred years prior.

Settlement had come slowly in this mountainous place and the second half of the 18th century was a troubled time. The massacre at the Moravian outpost at Gnaden Huetten in 1755 made matters worse. The massacre occurred during the French and Indian War, a time when some Native Americans, allied with the French in Canada, committed acts of violence against the European settlers after having been cheated of their lands through spurious land deeds and treaties. This led to an exodus of many of the few who had settled here. It wasn’t until after the Revolutionary War and that the region finally stabilized and settlers began to return.

Among these settlers was Philip Ginder, a hunter and mill operator. In 1791 he discovered deposits of anthracite (coal) on a mountain top near the upper Lehigh while hunting. He took his discovery first to Jacob Weiss of Weissport, and Weiss reached out to others in Philadelphia, leading to the creation of the Lehigh Coal Mining Company (LCMC). Though the deposits were extensive and easy to remove by surface quarrying, transporting the coal to market proved to be a task nearly insurmountable. For twenty five years the LCMC limped along, sporadically getting coal to Philadelphia, but not enough to make the company profitable. And so the LCMC failed, and the coal deposits remained mostly untapped. But the small amount of coal that did reach Philadelphia proved very important to American history- it was the seed from which the great coal rush would sprout, and the Lehigh anthracite would soon be fueling the Industrial Revolution.

White, Hazard and Hauto petitioned the state legislature to allow them to take on the project the LCMC had failed at. The legislators finally agreed to “allow them to ruin themselves” in the project, and so it was on that cold December the partners rode north.

North of Philadelphia they entered a land only sparsely populated, finding shelter at what few homes they came to. At the village of Bethlehem they found lodging in the sole tavern of the place. Beyond that the few farmsteads became more distant from each other as they went. From Lehigh Gap they followed a state road which followed the east bank of the Lehigh and soon reached the home of Jacob Weiss and Weissport. Weiss, a Colonel in the Revolution, had established his home and village at the place where the Moravian village of New Gnaden Huetten had been. New Gnaden Huetten was the successor to the village of Gnaden Huetten, site of the massacre. Now at the age of 67 years, Weiss found his health and eyesight failing, but still hoped to get some return on his investments in the coal lands.

After meeting with Weiss, the partners crossed the Lehigh and passed through the tiny village of Lehighton on the west bank. As the moved north, the valley narrowed and the steep mountain ridges towered a thousand feet over the river. About three miles above Lehigh-ton they finally reached their destination, a remote place with a stony creek emptying into the Lehigh, a place known as Little Spruce Swamp. This was the mouth of the Mauch Chunk Creek.

The only sign of the hand of man at this place was the rough road they followed and some ruined constructions of the LCMC. They turned from the river and followed the path of the Mauch Chunk Creek into a narrow ravine which eventually broadened into a pristine valley. They soon came to the first of two small assemblages of rough huts. The dwellers were those who had remained from the days of the LCMC operations.

They referred to their hamlets as Sodom and Gomorrow (sic), names given to reflect the harshness of their lives. Far from qualifying as villages, each consisted of only three or four huts. Rough cut planks formed the walls, according to White, and he was surprised to see some had a few panes of glass in their windows. The partners were welcomed by the citizens, finding warm shelter and sharing with them the bread they had brought from Philadelphia, a rare commodity in the mountains. Among the those people was a young man that White and Hazard had met before.

In 1813 Abiel Abbott had piloted one of the few LCMC coal arks that had survived the ride down the Lehigh and had made it to Philadelphia. The news of the arrival of the Lehigh coal made the rounds in Philadelphia, eventually reaching the ears of factory owners White and Hazard. They went to investigate and there met Abbott and procured some of the coal. From Abbott, they gained not just coal, but information on the source of that fuel far to the north. From this chance meeting an enduring relationship between the Philadelphia businessmen and the Lehigh mountain man came to be, a relationship that would continue for many years.

Abbott gave them a tour of the region, from the coal quarry on the mountain top to the road to the river opened many years prior by the LCMC. This road was found to be overgrown, eroded and useless. It was clear that much work needed to be done before they could ever hope to move coal just from the mountaintop the nine miles to river.

As 1817 turned to 1818, and winter turned to spring, White and Hazard made return visits. They made detailed surveys of the Lehigh, from its headwaters to the river’s mouth on the Delaware at Easton. The valley of the Mauch Chunk Creek was also surveyed in preparation for the construction of a much better road from the quarry to the river.

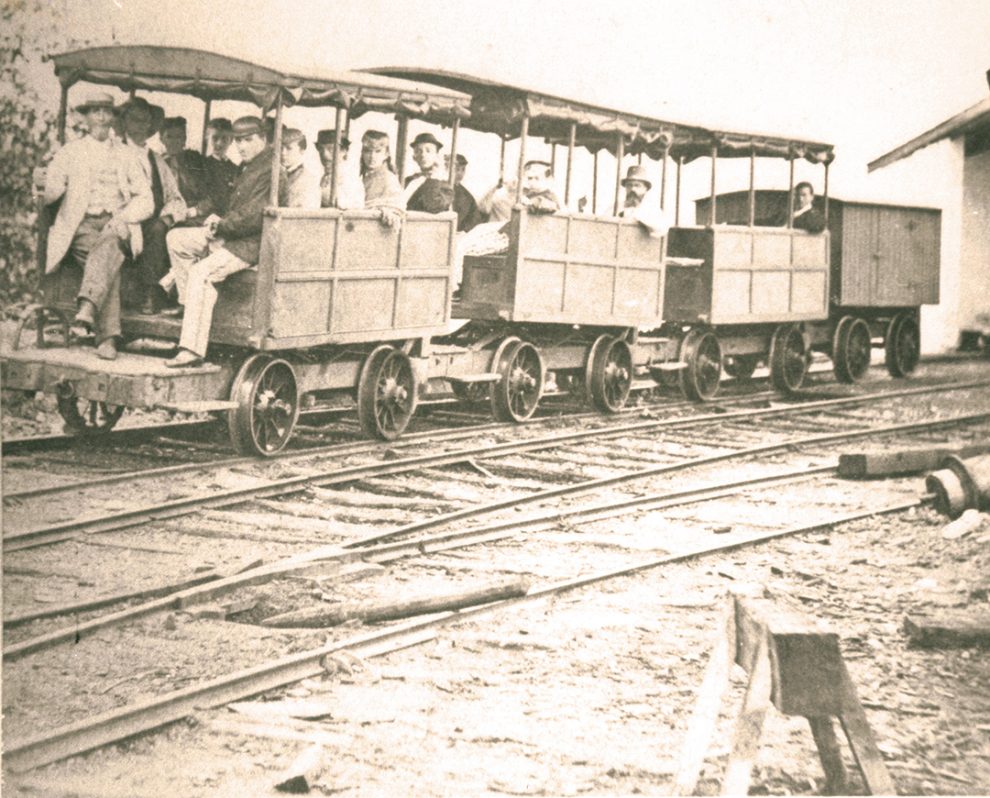

As spring turned to summer, the partners established “Whitestown on the Lehigh”, a collection of single story scows where the work crew could eat, sleep, and plan their work as they floated along the river, clearing a channel. These laborers were mainly unemployed sailors who had been recruited from the wharves of Philadelphia, hard men doing hard work in a remote and dangerous place. The three partners were taking a great risk dealing with this rough crew, and it was made clear to all there was no money at Whitestown; pay would only be received upon safe return to Philadelphia.

As the summer of 1818 began to draw to a close, the partners knew it was time to establish a base – or village – for their company. The site of the Lausanne Landing Tavern at the mouth of Nesquehoning Creek had been considered, but eventually rejected. Instead, a village was established at the mouth of the Mauch Chunk Creek at Little Spruce Swamp. This was the founding of our town, Mauch Chunk – later renamed Jim Thorpe.

Jack Sterling is a local historian and editor of The Chunker, The Mauch Chunk Museum & Cultural Center’s quarterly newsletter.

Add Comment